How I Reverse-Engineered a National Exam at 15 (And Predicted My Score to the Decimal)

In Sudan, your entire academic future hinges on one exam. Think SATs, but if the SAT was the only thing that mattered — no extracurriculars, no essays, no legacy admissions. One number determines everything.

The results announcement is one of Sudan's most anticipated national events. Top scorers become instant celebrities. Their names get broadcast on television. Government officials visit their homes. Strangers stop them on the street. For a few weeks every June, these teenagers become the closest thing Sudan has to national heroes.

In 2011, I scored 98.3%. That score stood as the national ceiling for over 12 years — only tied in 2023, never beaten.

I was from Kassala — a poor, neglected state on Sudan's eastern border, far from the capital where top performers typically emerged. No one from Kassala had ranked at the top nationally since the 1970s. Four decades of nothing.

But here's what most people don't know: I predicted that exact percentage months before results came out.

And I have the receipts.

The Prediction, Timestamped

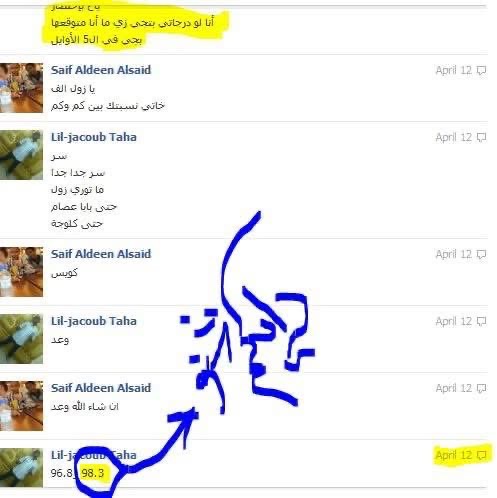

On April 12, 2011 — over two months before the June 24th announcement — a friend asked me on Facebook what percentage I expected. I told him it was a secret. "Very very secret. Don't tell anyone. Not even Baba Issam. Not even Kaloja."

He promised. So I told him my range: 96.8 – 98.3

That conversation is still up. Timestamped. The final result hit my upper bound exactly.

This wasn't confidence. It was calculation.

The Data Collection Phase

When I entered high school at 14, I started doing something unusual. I tracked down the previous year's top performers — kids who'd ranked 2nd and 3rd in the entire country — and started collecting data. I used MSN Messenger and a now-dead app called Numbuzz to gather their scores across every subject.

I was intimidated talking to them. I remember feeling a physical tremor when messaging Yousif, who'd ranked 2nd nationally, or Sajda, who'd ranked 3rd. These were celebrities in my world. But I kept asking questions.

A pattern emerged: Physics was consistently the weakest subject, even among elite performers. That insight gave me a three-year runway to over-index on the variable most likely to differentiate me.

One question haunted me as a freshman: why had no one from Kassala broken through in forty years? Was it resources? Teaching quality? Or just assumptions that had calcified into destiny?

The Hypothesis Testing Phase

There was conventional wisdom that one city — Medani — had some "magic formula" for producing top scorers. Sajda was from there. Khartoum dominated the top ranks, but Medani was a consistent second and had produced a few #1 students over the years. Maybe there was something in the water.

So I transferred schools to test the hypothesis directly. I lived with my grandmother's sister, enrolled in a private school called Makki Al-Tayeb, and spent a full year investigating whether the magic was real.

It wasn't. The teaching was actually further from the exam material than what I had back home. The only valuable thing I extracted was learning third-year physics curriculum a year early from the school's founder himself.

I returned to Kassala with a clear conclusion: there was no secret. Just preparation and strategy.

The Khartoum Test

But I wasn't done. The summer before my final year, I traveled to Khartoum for an exam bootcamp at Idris Foundation — one of the most prestigious test-prep institutions in the country, a factory for top performers. If there was any secret sauce, this is where I'd find it.

That's where I met Khaled Mahdi. He was the top student at Bashir Mohammed Saeed — a school with a track record of producing #1 national students. For me, he was a proxy. If I could measure myself against him, I'd know where I stood.

My read: he was strong. Really strong. But I felt I could do better.

The Contrarian Bet

When the Idris Foundation administrators realized what they had, they didn't let it go. They traveled across the city to meet my father and deliver their verdict: "Your son will rank nationally if he stays here. If he goes back to Kassala, he won't."

Khaled told me the same thing to my face.

The subtext was clear: kids from Kassala don't break through. That's just how it is.

I weighed their input. Then I trusted my own model.

Back home, I hung a sign in our family's sitting room where my study groups met: "Difficult does not mean impossible." I eventually stopped group tutoring and relied on targeted support from two teachers who believed in me — Mr. Hamza Abbas for Computer Science, who taught me the third-year curriculum for free during summer, and Ms. Awadiya Zayed for Chemistry.

The Strategic Edge

Here's how the scoring worked: four mandatory subjects (Math, Islamic Studies, Arabic, English) plus your best three out of four electives. Your final percentage was calculated from seven subjects total.

The science track required Physics and Chemistry, then you chose from Engineering Science, Computer Science, or Biology. Most students picked Biology. I took Computer Science — which my school warned against ("it fails students") — and added Agricultural Science as my fourth elective.

This gave me a buffer. I could absorb a hit on Physics (the subject I'd identified years earlier as the universal weak point) and still have it count, or drop it entirely if one of my other electives outperformed it.

The conventional wisdom was wrong. My analysis was right.

The Outcome

- Physics: 93 (the subject I'd identified as the key variable years earlier — it counted)

- Agricultural Science: 97 (lost points on obscure trivia — how many tons of sorghum does Sudan produce annually?)

- Final score: 98.3%

The exact upper bound of my prediction range. Posted publicly. Timestamped. Two months in advance.

That number held as the national benchmark for over twelve years. It was only tied in 2023. Never surpassed. And it came from a state that hadn't produced a top national performer in four decades. The student who came in second was from Khartoum.

Why This Matters

This wasn't genius. It was systems thinking applied early. At 15, I was:

- Gathering primary data from domain experts (even when it terrified me)

- Identifying high-leverage variables through pattern analysis

- Testing assumptions empirically rather than accepting conventional wisdom

- Making contrarian bets based on independent analysis

- Building conviction strong enough to publish predictions publicly

The same approach got me to the top 0.5% globally in competitive gaming. It's the same pattern I apply now.

Some people see 98.3% and think "smart kid." I want you to see what it actually was: a three-year research project executed by a teenager who refused to accept that geography was destiny — and who had modeled the system precisely enough to call his shot to the decimal.

Forty years of silence from Kassala. Then one kid who decided to reverse-engineer the game.